MIT scientists reveal why water drops move faster on a hot, oil-coated surface

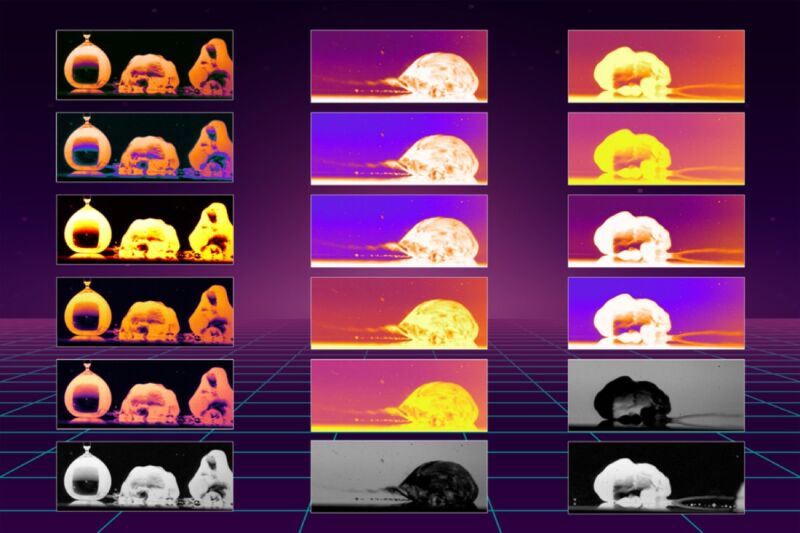

Enlarge / Researchers have determined why droplets are propelled across a heated oily surface 100 times faster than on bare metal. The images above reveal the mechanisms that cause the rapid motion. (credit: Kripa Varanasi/MIT News)

There's a classic 2009 Mythbusters episode in which the hosts demonstrate how someone could wet their hand and dip it ever so briefly into molten lead without injury. The protective mechanism is known as the "Leidenfrost effect," and it could one day prove useful for microfluidic devices, particularly in microgravity environments, among other applications. We're one step closer to achieving those applications, thanks to new insights into the phenomenon uncovered by MIT scientists. They described their findings in a recent paper published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

As we've reported previously, the Leidenfrost effect dates back to 1756. That's when German scientist Johann Gottlob Leidenfrost observed that, while water splashed onto a very hot pan sizzles and evaporates very quickly, something changes when the pan's temperature is well above water's boiling point. When that happens, Leidenfrost discovered, "gleaming drops resembling quicksilver" will form and will skitter across the surface.

In the ensuing 250 years, physicists came up with a viable explanation for why this occurs. If the surface is at least 400 degrees Fahrenheit (well above the boiling point of water), cushions of water vapor, or steam, form underneath the droplets, keeping them levitated. The droplet can skitter across the surface with very little friction. The Leidenfrost effect also works with other liquids, including oils and alcohol, but the temperature at which it manifests (the "Leidenfrost point") will be different.

Read 9 remaining paragraphs | Comments

https://ift.tt/3iQsImw

from Ars Technica https://ift.tt/3m9lv3e

No comments